Theophysics: Exploring the Friendship of Physics and Theology

Jan 14, 2026 | By Nicolas Wyszkowski MY ‘26

The great minds that developed modern physics were in near unanimous agreement that physical law (and the universe more broadly) was not the result of a Creator, at least not one interested in human affairs. Nobel prize-winning theoretical physicist Eugene Wigner remarks in his famous essay The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences that, “the enormous usefulness of mathematics in the natural sciences is something bordering on the mysterious… there is no rational explanation for [it] [1].” What Wigner is saying here is very deep: the beauty, rationality, and simplicity of physical law evidenced in its ability to be mathematically well-approximated does not have a rational explanation.

This piece will explore the Christian response to this point through an examination of theophysics, a field of thought that seeks to unify physics with theology.

In particular, through the examination of some of the divine attributes evidenced in physical law, namely omnipresence, omnipotence, and invisibility, we will hopefully see a very natural friendship between physics and theology, which can provide a rational basis for the mysterious usefulness of math in the natural sciences.

We will begin with a definition of physical law, followed by an overview of God’s role as Creator in Christian teaching. We will then discuss attributes of physical law that can be grounded in God’s authorship of the universe, with the goal of seeing the beautiful harmony between the material and spiritual, the physical and the divine, that theophysics provides.

Part I: What is physical law, and how does it relate to math?

Broadly speaking, physical law is the set of rules governing the regularities observed in the natural world. These regularities are observed at all scales, and even in random events: from radioactive decay to galactic orbits around central black holes, from the scattering of light off a prism to the apple that fell on Newton’s head, we observe recognizable patterns of behavior in all areas of life. As Wigner (and generations of physicists before and after him) realized, mathematics is tremendously effective at describing physical law, to the point where it is natural to think of mathematics as the language of physics. Here, though, we need to be careful not to confuse the words for the things they represent. For simplicity, we typically associate physical law with the corresponding equation (or set of equations) by which we describe it mathematically, but this is not technically correct: equations don’t make planets move or electrons jump. Instead, equations help us put into “words” the workings of the physical universe, providing physicists a common language with which to exchange ideas and make predictions about the underlying nature of reality. The reason it is important to distinguish equations from the physical law they describe lies in the iterative nature of physics: as we develop more complex mathematical and experimental machinery, we can probe deeper into the fabric of the cosmos. Oftentimes this forces us to revise previous theories as we discover new phenomena (the replacement of Newtonian gravity with Einstein’s theory of general relativity is an excellent example of this kind of productive revision, see [2] for a good discussion). This does not mean the nature of the universe has changed: it means the way in which we “speak” about it in the language of math has changed. So, as we discuss divine attributes which are revealed in physical law, we must discuss the underlying reality which mathematics approximates so beautifully, and not the mathematical equations themselves.

Part II: God as Creator and Sustainer

In the opening chapters of Genesis, the ancient Hebrew writers tell the account of how God molds, out of nothingness, a universe of beauty and order and power. When I try to think of this scene, I listen to Hans Zimmer’s “Cornfield Chase” and imagine watching the most startling and incredible burst of light come from nothingness, a supernova springing forth from the abyss [3]. He’s setting in motion everything that will happen, creating all energy and matter by the power of His Word and determining how they will interact. Far from being a passive observer of the creation of the cosmos, God is intimately involved in its birth, giving the cosmos form and substance. The New Testament furthers this discussion by including Jesus in the creation picture. John 1 opens with Jesus’ role in creation, saying in verse 3, “Through him all things were made; without him nothing was made that has been made” (NIV). Paul continues this idea in Colossians 1:16-17, saying that in Jesus “all things were created: things in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible… all things have been created through him and for him. He is before all things, and in him all things hold together” (NIV). We see then that Christian teaching espouses the Triune God as Creator and Sustainer of the universe, and as such, we expect to see His nature reflected in creation.

Part III: Divine Attributes Evidenced in Physical Law

If we hold that there is a friendship between physics and theology, then we need to put parts I and II together, grounding the regularities of the universe in God, their Creator and Sustainer. Three key attributes of God that are evidenced in physical law will help us to do this

Omnipresence

Omnipotence

Invisibility

Omnipresence, in the sense meant by classical Christian teaching, refers to the fact that God “is everywhere and in every now” [4]. It is a spatiotemporal saturation, a state of constant being. In practice, all physicists adhere to the omnipresence of physical law, which is a highly nontrivial (but incredibly important) attribute. The omnipresence of physical laws is so foundational to physics that Wigner points out that without it, physics would be impossible [5]. Consider the absurdity of a particular patch of grass on which gravity was nonexistent. It’s such a repulsive idea that this patch of grass could somehow be free from the law of gravity that scientists would immediately begin testing to discern a physical reason for this “miraculous” grass. Going a step further, imagine if the strength of gravity on that patch of grass varied over time: one second you’re floating above the ground, the next your feet are glued to the surface. Instead of throwing up their hands in dismay, physicists would probably start measuring the gravitational field to see if it was described by cosine or sine! We simply cannot fathom the idea of physical law as fickle and changing; it is intuitively seen to be omnipresent. The Christian grounds this attribute of physical law in God’s own omnipresence, seeing it as a natural byproduct of the fact that physical regularities are His observable word of governance.

A second important attribute of God evidenced in physical law is omnipotence, “the perfect ability of God to do all things that are consistent with the divine character” [6]. In the case of physical law, this is intimately connected with omnipresence: because physical law is valid everywhere in space and time, its power over the physical universe can be thought of as absolute. Under regular circumstances, there is no way for anything in the universe to interfere with the governance of these laws. One may note that God’s omnipotence and the omnipotence of physical law as described seem to contradict each other, in the sense that if physical law is omnipotent, it would restrict God’s own power by limiting His actions to those that obey physical law. This is a spurious contradiction though: God freely working within the constraints of physical law is not an abridgement of His power or freedom, but a voluntary choice in alignment with His character (a choice that greatly benefits us as humans, since we don’t have to fear the utter collapse of physical law at any moment due to random acts of a capricious god). In this sense, the omnipotence of physical law and God’s omnipotence are not in contradiction, but are in fact complementary, allowing us to reasonably ground the former in the latter.

The third attribute of God that applies to physical law is invisibility, and it carries great methodological significance: how do we discover truths about God and physical law if they cannot be directly observed? The answer is that each can be known by its effects. Because of the invisibility of physical law, we discern its existence and properties through natural events and experimentation instead of via direct observation. Similarly, though God is invisible, we can discern His existence and presence via indirect means, such as the existence of an ordered universe or answered prayer. It is crucial to note that in both cases, despite the attribute of invisibility, we are justified in seeking truth about the subject of our search: despite the impossibility of direct observation, we can still come to genuine, deep knowledge of both physical law and God. This invisibility also inspires a sense of awe and wonder for the physicist and theologian alike: we, the visible, the material, get to study the invisible, the immaterial. More than merely studying these things, we get to see the fruit of our faith in them as we construct complicated devices that rely on fundamental physics or experience the joy of a life radically changed by God. Both of these wonderful, tangible experiences are grounded in invisible realities that rightly deserve our study and faith.

Part IV: Physics and Theology, Friends

Where, then, does this leave us with respect to Wigner’s quote at the onset of the piece? Well, we have seen that physical law has some divine attributes, which can naturally be grounded in God as the Creator and Sustainer of the universe. The deeply theological nature of physics that follows from this grounding is the basis of the friendship of physics and theology: there is a deep, amicable bond between the two fields that flows from Christian creation doctrine. By establishing this friendship, we are justified in saying that the rational structure of the cosmos, the logos, is grounded in God as its Architect [8]. If the universe has this underlying rational structure, then it’s plausible there is a language to describe the structure, at least approximately, and that language, as far as we know, is mathematics.

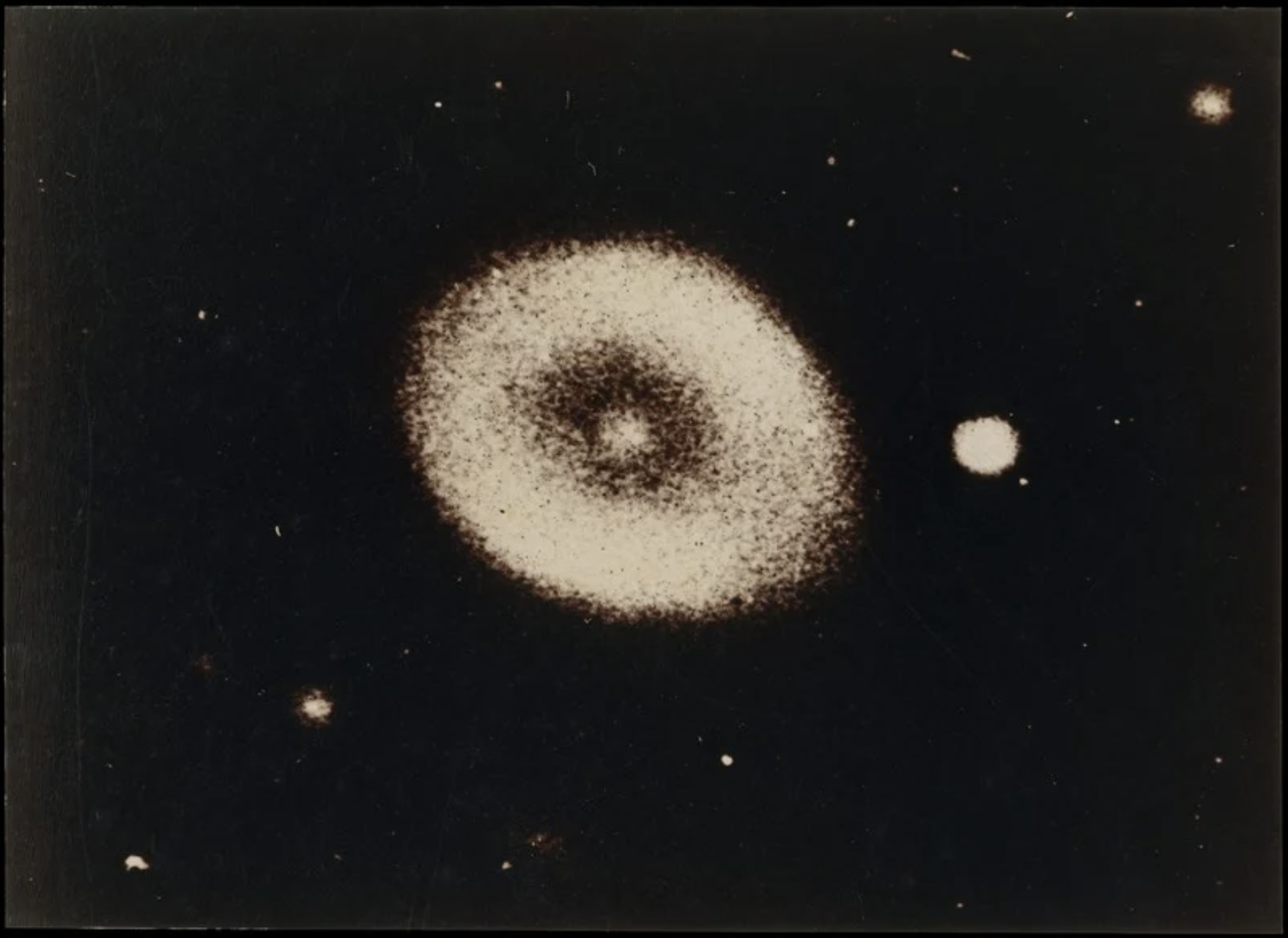

The ultimate picture we get from the friendship of physics and theology is that from the invisible God pours forth an amazingly complex and intricate universe governed by invisible physical law, which we can describe amazingly with mathematics. With pen and paper we can explore the mysteries of the smallest particles and largest galaxies, and with lifted hands we can ponder the One responsible for these mysteries. The physicist and theologian alike have the wonderful privilege of seeking out the invisible, the mysterious, the fundamental, a privilege which is a gift from God that, apart from Him, cannot be rationally explained.

[1], [5] Wigner, Eugene. The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences. 1960.

[2] Wikipedia Contributors. “Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 25 Feb. 2025.

[3] Zimmer, Hans. Cornfield Chase. 2014.

[4], [6], [7] Oden, Thomas C. Classic Christianity: A Systematic Theology. HarperCollins Publishers Inc, 1992.

[8] Alex O'Connor. “Why This Oxford Mathematician Is Confident God Exists | John Lennox.” YouTube, 22 May 2025.