Immortals

Jan 14, 2026 | By Gavin Susantio YDS ‘25

What do humans, elves, and God have in common? They’ve been storied throughout the ages as impossible friends. But the history of the strangest friendships, no matter how unlikely, may be the most human stories ever told. When the divine befriends the mortal, or the machine the human, a sacred bridge forms between the finite and the infinite. Across great fiction, the relationships between humans and robots, elves and dwarves, and gods and creatures share a striking feature: in each pair, one kind of being is immortal.

When I first studied classical literature, I was surprised to find many ancient philosophers writing about friendship in their treatises on ethics and the cosmos, including the notion that true friendships can only exist between equals, such as two almost identically virtuous souls. But rarely can we find, let alone pick up, modern books on the art of friendship. On the other hand, ancient writers like Cicero hints at a cosmic dimension of friendship and writes on the music of the spheres as harmonious and virtuous bonds.

I will now explore how the friendship of immortals can both enlighten and be enlightened by the friendship of mortals, especially in Dante’s heaven, Frieren’s earth, and the story of the Incarnation.

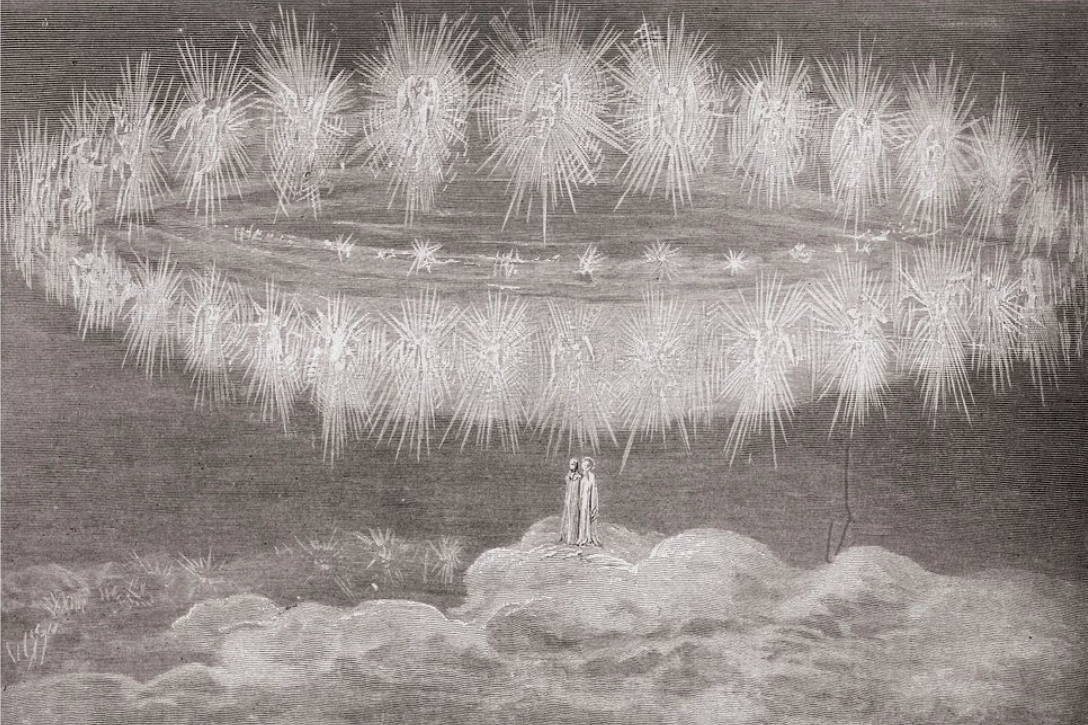

I. HEAVEN: MUSIC OF THE SPHERES

In Dante’s Paradiso, the saints dwell in the heavens and hymn songs of grandeur. The symphony of immortals is like a “horologue,” a medieval clock with intricate movements that mirror the solar system [1]. Each wheel turns with its own unique rhythm, yet they work together in concord and mathematical beauty. Paradiso itself is a harmony of seven celestial spheres, including the moon, the planets, and the sun. Thus, the cosmos and the saints are common in this horologian way.

There is, as the ancients believed and the medievals explored, a music to and of the heavens [2]. The friendship of the heavens outlasts us. The music of the spheres inspires us. Friendship itself can be described in cosmic terms, such that a harmony between souls is analogous to the harmony among planets.

Dante’s heaven resounds with this so-called music of friendship. Each saint voices a different melody yet is bound in one concord. This is called a polyphony—many independent melodies forming one simultaneity. Even former rivals with very distinct characteristics become eternal friends, such as between Bonaventure (a Franciscan) and Aquinas (a Dominican). The Franciscan ideal is marked by the active life or social justice, while the Dominican ideal the contemplative life or intellectual scholarship. Each prizes a different voice, yet this rivalry intensifies their friendship: in Paradiso, Bonaventure praises the Dominican namesake, St. Dominic, and Aquinas praises the Franciscan namesake, St. Francis of Assisi [3]. Differences don’t dissolve but join into polyphony or harmony.

Dante, then, poeticized what the ancients theorized. Cicero attributes to Pythagoras the saying that “friends hold all things in common [4].” The Greek and Roman philosophers viewed friendship as a topic of philosophical inquiry, describing how friendship can and should contribute to virtue, happiness, and society. Their ideals actually dominated Western reflections on friendship until the 18th century [5]. Cicero himself wrote the Dream of Scipio, a precursor to Dante’s cosmic heaven, which describes how the celestial spheres are music, as “cosmos” means “order” in Greek that implies something as intelligibly and beautifully harmonious. A divine order, including Cicero’s idea of friendship as a total concord, harmony, or agreement of feeling in heaven or on earth, are reflected in the saints in Paradiso.

We now have an example of friendship between immortals.

But immortals don’t only dwell in Paradiso. In fantasy literature, we are given a glimpse of immortals that dwell on earth. J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle-Earth, for instance, offers us a glimpse of the immortal psyche through elves, who coexist with human beings. I myself have always wanted to know what it’s like to be one of them or at least see the world from their perspective in detail. This is why Frieren: Beyond Journey’s End is the perfect series for Tolkien fans who share this curiosity.

II. EARTH: FRIEREN THE IMMORTAL

Frieren the elf is an extremely powerful mage, yet she’s small, quiet, and detached from human society. When she’s around, no one knows that she’s an “over-powered” character. But everyone knows she’s immortal. (Her pointy ears give it away.) And for a thousand years, Frieren has lived. She has a life that outlives our lifetimes.

Frieren the series surprised me because it defies expectations in anime and my Tolkien-bred skepticism. Why would anyone create another fantasy series? But Frieren doesn’t imitate; it reimagines. It embraces all the familiar threads and tropes of medieval fantasy—magic, quests, archetypes—yet weaves in something completely new. It was helpful for me to view a series like Frieren in its own right, not as another “manga” or “anime,” but a genre-reviving series that’s become a dark horse classic by approaching fantasy in unique ways.

The personalities of most immortals in anime swing to opposite extremes. They’re either (A) too human: immature, impulsive, “hangry,” or (B) too divine: forever elegant and untouchable. But Frieren asks a subtle question, namely, what is the true physiology and psychology of an elf? How does one live if time is endless?

Beyond Journey’s End

To my delight, the show began with what encapsulated the subtitle, “Beyond Journey’s End.” In the first issue and episode, Frieren and her fellowship of four—Himmel the Hero, Heiter the Priest, and Eisen the Dwarf—have already completed their 10-year quest. What’s supposed to be the end of the story is its beginning, moving the tale beyond the journey’s end. They’ve returned home after defeating the demon king, and they’re “immortalized” as heroes. Statues were erected, legends were told, and Frieren still looks young as ever. But that decade-long journey was only a blip in Frieren’s life. It was 1/1000th of her lifetime. Hearing her describe it as a “mere 10 years” was astonishing [6]. So, she’d casually visit her friends once every 50 years and eventually came upon Himmel—the radiant, charismatic, human hero—in his frail old age.

Shortly after, Himmel passed away. And that was the moment when Frieren, the serene and detached, wept for the first time in centuries. It finally pierced her.

She must learn how to be human. Or at least value the world and others like humans do. Where there is friendship, there is a risk. The risk of losing. The ache of parting. But with that risk comes the beauty and weight of every moment. Having experienced grief, she learns how to love despite that inevitability. She reluctantly but then willingly takes the human students of Heiter the Priest and Eisen the Dwarf on a journey towards finding heaven and reuniting with Himmel the Hero. In this new journey towards the beyond, she tries to value gift-giving, cherish old memories, and slow down time. As the series unfolds, Frieren’s sense of time is “catching up” with ours. The first episode covers half a century; the next, a few years; then weeks; then days. Eternity narrows until it touches human mortality. And this is exactly what resonates in another story, namely that of the Incarnation or the “Holy Immortal.” And here, in the Christian lifeview, is the plot twist: in the grand narrative of everything, we mortals are immortals.

III. HEAVEN & EARTH:

WE MORTALS ARE IMMORTALS

This is not figurative or metaphorical. The cosmic narrative of God and creation speaks of our bodily resurrection and a new heaven and earth that are meant for friendship that is everlasting, much like Frieren’s. We are, in a participatory sense, elves. We are meant to endure beyond our journey’s end.

However, this doesn’t make the present trivial. In fact, the present becomes luminous. We are not to take for granted our lives and friendships. We are to be more human, just like Frieren the elf learns how to be human: not to neglect the lives of others and instead attend to friendships that for her used to be fleeting and irrelevant, to love in light of differences, and to let every ordinary or mundane act carry the weight of eternity. Frieren’s life becomes more rich. She lives a philosophy of immortality that embraces all aspects of mortality. So—and here’s the paradox—immortality does not and should not undermine mortality. Immortality begins today.

By now, we’ve covered the friendships of immortals in heaven and immortals on earth. But we haven’t yet covered the friendship of the Holy Immortal, who is beyond heaven and earth, and who at the same time befriends creation.

Holy Immortal

In the famous, ancient Orthodox hymn called the “Trisagion,” God is referred to as the Holy Immortal, but in a technical sense. Holy entails that it’s a different kind of immortality than ours, which theology calls eternality. God is eternal, meaning outside of time; and this is opposed to everlasting, meaning enduring forever in time, such as spatio-temporal creatures who are immortal. Yet in the Incarnation, God becomes human. The Holy Immortal dies and rises from death and sanctifies time by entering our temporal world. The Beyond-Who-Became encounters the mortality of others and weeps alongside them [7].

Returning to the ancient Greek philosophical idea that true friendships can only exist between those of equal virtue and statues—the Holy Immortal undermines this very notion through the Incarnation, in which the Eternal, while being greater than all beings, participates in the world of temporal yet everlasting beings. The Eternal elevates the friendship between the human and the divine as not only possible but also the highest form of friendship. And even the word “friendship” ultimately fails to describe such a relationship. In the new heaven and earth, the bond between the Holy Immortal and us immortals are envisioned in the Scriptures as a relationship beyond friendship, namely the most intimate extension of it: marriage [8].

The Holy Immortal does not lose perfection through the marriage between the human and the divine. Rather, it shows that the perfection of the Holy Immortal (who Dante calls “the Love that moves the sun and other stars”) includes the capacity and reality to love the imperfect [9]. This is so by rejoicing with those who rejoice, weeping with those who weep, experiencing betrayal and loyalty, and sacrificing one’s entire self for the life of the world.

For the philosophers, true friendship is measured by equality. For the immortals, it’s measured by elf-giving. So, what does an elf and God have in common? The immortal elf survives all her mortal companions, learning to treasure finitude and vulnerability and “consecrating” memories as sacred. The Holy Immortal also shares in joy and grief with those who die. But death, in both Frieren: Beyond Journey’s End and The Book of Revelation, is only the bridge to cross from life to life.

In the series, the scriptures, and Dante’s Divine Comedy, friendship may be everlasting, but mortality teaches the immortal how to truly and fully love it. Immortality is learned through mortality. And to live immortally is to live attentively, for immortality is not a promise that begins at death but rather begins now. And the music of the heavens even begins with the smallest notes we dare to voice and polyphonize together on this earth.

[1] Dante Alighieri, Paradiso, Canto X, lines 139–148.

[2] See Boethius, The Consolation of Philosophy, Book V.

[3] Dante, Paradiso, Cantos XI–XII.

[4] Cicero, De Legibus, Book I.

[5] Dirk Baltzly and Nick Eliopoulos, “The Classical Ideals of Friendship.” In Friendship: A History, edited by Barbara Caine, Acumen Publishing, 2009, p. 2.

[6] Kanehito Yamada, Frieren: Beyond Journey’s End, “Chapter 8: One One Hundredth,” Shogakukan, 2020, p. 17.

[7] John 11:35.

[8] Revelation 19.

[9] Dante, Paradiso, Canto XXXIII, line 145.