Tree Rings of the Soul

May 1, 2025 | By Raleigh Adams YDS ‘26

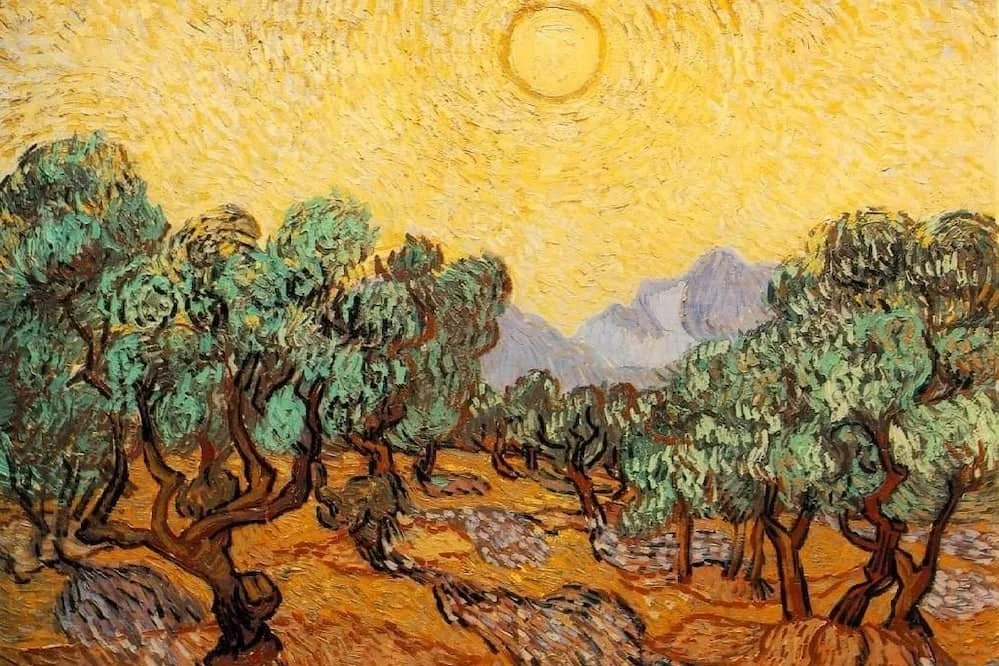

Vincent Van Gogh, Olive Trees with Yellow Sky and Sun, 1889

“What if the sadness never leaves?” That’s the question I couldn’t stop thinking about after ChatGPT told me my patterns and blind spots based on our chat histories.

Number one was “your emotional residue lingers”; that “your heartbreak still shows up—beautifully, honestly—but it may color other aspects of your life more than you intend. Whether it’s in your theology of longing, or your cautious approach to new people, there's a tension between your mind's clarity and your heart’s ache.”

This struck a chord to my very core, an ache I knew to be there but had avoided giving a name to. Like how trees hold the rings of all the prior versions of themselves inside their trunks, so too is my sadness and grief, my emotionality, within me. They are my personal tree rings—marks of former selves and lingering experiences held quietly within.

I think this is the case for many people.

However, in the grand horizon of a life, this seems like an awful weight to carry, heavy and burdensome on one’s shoulders and soul alike.

Modern man lives in a world obsessed with healing, with moving on, with becoming “unbothered.” Therapy culture emphasizes “closure” above all else, Instagram reels that declare “you owe no one your old self,” and an overarching pressure to be a post-pain version of yourself.

But what if there is no magic moment where these emotions and memories are resolved? What if life and growth are simply adding to this weight, until you are crushed by it? What if transformation into a better self never comes, or not how it's wanted? Scariest of all, what if carrying the ache well is holiness?

There is an idea of the soul as “wounded” by love, memory, and longing—but that God uses even wounds as openings. Saint Augustine works from this place within his Confessions, a model of the discrepancy between the mind's clarity and heart’s ache. The bishop was no stranger to grief: mourning the death of his friend, his career and ambitions, and his mother in the span of only a short amount of time.

The language Augustine uses to describe the grief he carries is bodily and visceral, saying of the death of his friend that “At this sorrow my heart was utterly darkened, and whatever I looked upon was death… My eyes sought him everywhere, but he was not granted to them; and I hated all places because he was not in them.” [1] Life, for Augustine, is one of grief and unease.

Augustine never stops being restless, even after baptism the transformation does not bring immediate peace. Rather, it brings the ability to use one’s broken past, to turn emotional residue into a becoming. He doesn’t move on, not in the modern sense, but rather moves within.

For Augustine, memory is not just a place of recall—it is the terrain of encounter, where the soul begins to remember its Maker.

In his exploration of memory, Augustine notes that “For without rejoicing I remember that I was once joyful; and without sorrow I recollect my past sorrow. And that I once feared, I review without fear; and without desire I call to mind a past desire.” [2] Augustine comments that he can remember feelings without currently feeling them. In the “vast court of memory,” he finds the echo of past joys, pains, fears, and longings, yet as images rather than live emotions. He can exist in the emotional residue, make sense of it. With time and reflection, one can recall sorrow as a memory. It becomes something that can be observed from a distance, no longer overwhelming in its immediacy. The emotional intensity has faded, yet the fact of the feeling remains accessible. Memory both stores and domesticates our past emotions – allowing us to remember our grief or pleasure even when we no longer actively grieve or desire. Perhaps Virgil was right, “forsan et haec olim meminisse juvabit,” that one day it will please us to remember even this.

Tree rings are like memory. They form through seasons of joy and suffering. They are not bad. They are the conditions of growth. Even Christ had “tree rings,” or rather, wounds, after His passion: “See my hands and my feet, that it is I myself.” [3] Resurrection and new beginnings do not mean forgetting the Cross or emotional erasure. Rather, the weight of emotional wounds sanctifies us, an active becoming we carry constantly, rather than a singular event.

Perhaps the tree rings aren’t only burdens, but testimonies. Signs not of failure to heal, but of a soul that has loved, and suffered, and kept growing. Perhaps holiness is not a forgetting, but a remembering transformed by grace.

[1] Saint Augustine. Confessions. Book IV, ch. 4.

[2] Saint Augustine. Confessions. Book X, ch. 14.

[3] Luke 24:39.