Inclusivity in Worship

October 27, 2019 | By Anthony Hejduk, MY ‘20. Anthony is majoring in Philosophy.

What does it mean for a worship space to be inclusive? Or more generally, what does it mean for a Christian community to be? As the Church across the world grapples with declining membership and increased fragmentation, especially in the West, this question is on the forefront, maybe more so now than ever before. But what is inclusion? And whom is it for? It seems to me that there are a few different senses by which one can understand inclusion. For brevity’s sake, I’ll limit myself to discussing three of them: ideological inclusion, experiential inclusion, and dispositional inclusion.

Ideological inclusion in worship is the idea that a service should encompass as many different beliefs as possible, and should not make statements which would exclude different belief systems. This is the kind of inclusivity in worship which might be sought after in a Unitarian church. Regardless of the individual beliefs that one holds, the worship service will be geared towards allowing a general kind of religious expression that does not require specific beliefs to be fruitful. While this might be sought in worship services for other religions or worship service analogues, like baccalaureates or certain kinds of weddings or funerals, it seems that this cannot truly be present in authentic Christian worship. True, there is real value in minimizing the importance of certain political, economic, or nationalistic beliefs in worship, to the extent that division is not created in the body of Christ. But the belief that Jesus Christ, the Son of God, rose from the dead and through His sacrifice we may be justified before God, must be present and conveyed in Christian worship if it is to truly be worship in the Christian sense. As exclusive as beliefs like this might be, and as uncomfortable as they might make worship services for those who do not hold them, they are non-negotiable for members of the Christian faith. The other forms of inclusion, however, are not so simple, and may legitimately divide honest members of the Christian community.

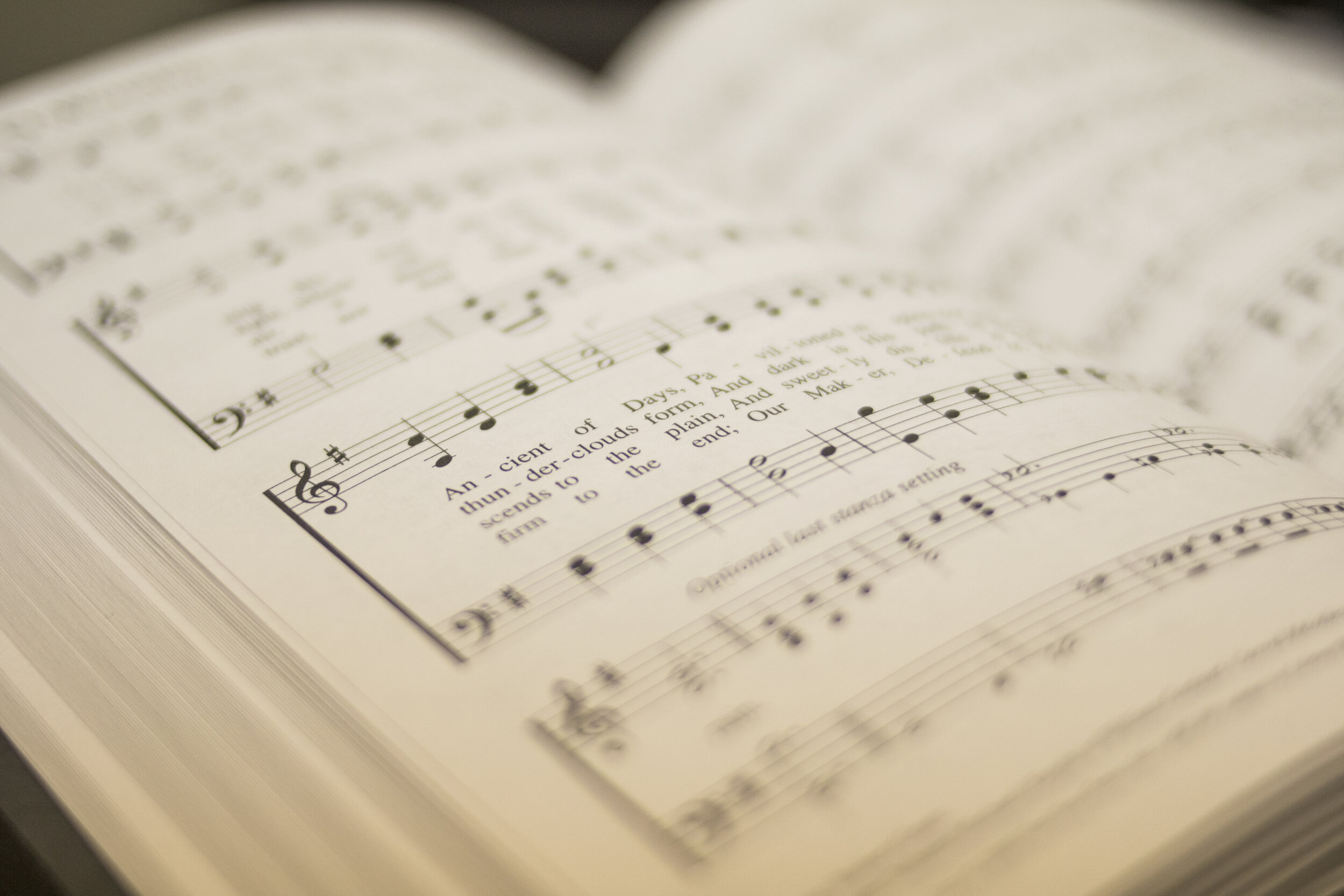

Experiential inclusion in worship is the idea that a service should require no background in that specific worship practice to participate. There would be no kind of assumed knowledge present about things like memorized prayers, specific actions like kneeling at specific times, or other aspects present in a formal liturgy. Many protestant churches more or less achieve this, as they require little to no background to participate, and if there is specialized knowledge, it is usually minimized or in some way explicitly broadcasted (worship lyrics being put on a tv, for example). Discussions of inclusivity often focus on this issue, and not without reason. The idea that newcomers might find a worship space to be a confusing and unwelcome place is a natural concern, and making genuine efforts to alleviate this is laudable.

Dispositional inclusion is the most complicated of these terms, and it refers, broadly, to the ability of a worship service to include members with broadest reach of natural reactions to and tendencies for specific kinds of worship. The easiest way to understand this concept is to look at what might violate this kind of inclusion. Worship that expects a kind of reaction from the congregation to be legitimate, anywhere from raising one’s arms and swaying to speaking in tongues, prizes a kind of dispositional reaction to stimuli and a certain expression of this reaction. Worship that likewise expects a mere silent reaction when some would want to make their praise clear and vocal also excludes, albeit in a different manner.

Putting ideological inclusion aside, is there a kind of worship that is experientially inclusive, dispositionally inclusive, and still fruitful? For me, a high church service conducted in an ancient language is the extreme between complete dispositional inclusion and experiential exclusion, such as a Latin or Greek Orthodox mass. Nothing is required from the congregation in worship except attention and prayer; the only participation in worship is the communal embrace of God or reception of the Eucharist, none of which requires a specific reaction for inclusion. Hypothetically, members from all over the world, with no common language, class, culture, or even reactive disposition, could worship together in this manner. On the other end of the spectrum is a worship service that is essentially reactive and participatory, with worship music and altar calls that are geared towards new members, no formal prayers that would require prior knowledge, and an atmosphere that closely mimics common experience, like lectures or concerts.

While I think that a medium can be found between these two extremes, I would caution too zealous of an approach from the side of what is usually meant by inclusivity, experiential inclusivity. The idea that these high church worship services can be made enjoyable and fruitful by moving to a more engaging and participatory worship style might be true for people with generally similar natural dispositions to the same style of worship, but as soon as one is prized, those who naturally react in a different way would be excluded. And as a service becomes less formal, it becomes less universal as well: Catholics can genuinely worship in any Catholic church in the nation, and in many cases, the world, with only a basic familiarity with the mass, thanks to its universal formality. A church that seeks to include new members by removing formal aspects of liturgy ignores the specific kind of new member outreach that a formal, geographically inclusive, that is, universal, liturgy provides.