Capturing Holiness

Feb 13, 2026 | By Isaac Oberman DC ‘26

Eckhart frowned. He looks fine. That was good enough for a typical commission; standard artistry would cut it for most clients. The Cathedral, unfortunately, was no common patron. The icon needed to be holy yet approachable, eye-catching yet not obtrusive, on fire but not hot. Altogether, it required a perfection of his craft. And although the features were striking and the gravitas palpable, St. Boniface still felt void. This job needed more thought. The cathedral expected more for the price, Eckhart expected more of himself, and Boniface simply was more than the painting purported him to be. The piece wasn’t finished anyway, owing to the missing nimbus over Boniface’s tonsure. What an absurd image that would be, a ring of gold around his ring of brown hair.

He put down his brushes and crossed the cathedral to get a wider view. Not much better. The monk was poised in an arcing motion, axe wedged into an oak tree, serenity (or apathy, who knows at this point) painted on his face. The habit, bulky and unflattering, captured none of the body’s silhouette through its swing, adding a comical shape to the mass of brown fabric. The light from the opposing windows fell in weird spots, accentuating the sleeves and the axe but leaving the rest of the image dusky. Boniface’s face, unlit, was youthful. The icon tried to capture the scene of St. Boniface cutting down the Donar Oak, a sacred pagan tree. The image was supposed to represent the wisdom and power of Christianity toppling the strong tree-idol, with an older Boniface as the perfect exemplar of wisdom and strength. Instead, a younger Boniface made the monk seem brash and immature, not a calm advocate of truth but a naive child hacking indiscriminately in his boyishness. Everything was just a bit off. Askew. And Boniface still lacked his halo, but there was still a bit of time. I have a week. They should know better than to ask me to work while the birds are dancing just past the stained glass.

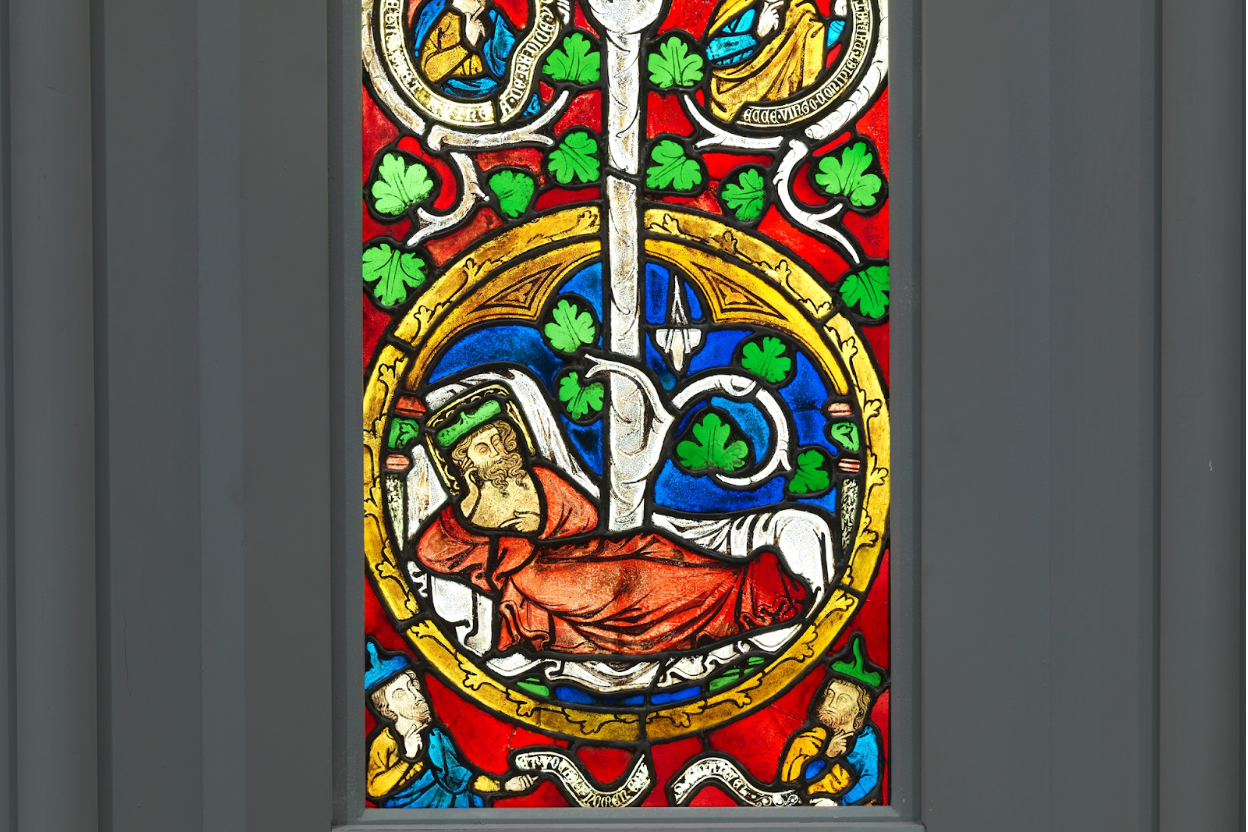

As he exited the narthex and walked towards the nearest cafe, the bells above him sang the forenoon’s end. His routine for the last few weeks of this project entailed getting to the church early and starting his long lunch when the shadow of the maple outside crossed over the Jesse window on the left wall. The window depicted the ancestors of Christ as a tree, with King David’s father resting at the bottom, the passive patriarch of the divine lineage. If Jesse gets to sleep in the shade of his tree, so can I. And so he would pass into the street, snag a strudel, and amble towards the nearby park to look for the faces of the clouds. Nobody questioned him or called him out on his sloth; he had artistic musing for a license. By the time he woke up, it would be late afternoon. Collecting himself and brushing off the crumbs, he would begin his stroll back towards the cathedral, whistling along to the tunes of busking musicians with fast fingers. On his arrival, he would take a deep breath and reenter the ring with Boniface. It was hard to say who suffered more blows, Boniface from the brush or Eckhart from frustration.

The route to the bakery had become a habit by this point. For the last week, the demolition of the paper supply merchant supplied the symphony for his walk. He bought most of his canvases there, but there was no sadness for Eckhart in its destruction; he was glad to let it go. As he rounded the corner, he found the construction crew chuckling at some charade acted by the foreman while they took sledgehammers to the walls, light streaming in where missing bricks once stood. He hummed along with the percussive rhythm of demolition, interrupted by raucous laughter. The cacophony did little to ingratiate them with their neighbors - not that they seemed to care. Any time a ruffled passerby offered an annoyed countenance, one of the crew would initiate an impression that threw the group into hysterics, and they would resume at fever pitch. Their hands flung up in laughter and down in wreckage. Each swing of hands lined with cracks - and dirt - and soot - and concrete - and age split the rock and split their skin. As he walked by the scaffolding, the workers waited to see if the painter would offer them some funny face to mock. Eckhart offered only a thin smile, and their gruff grunts conveyed sincere disappointment in his attempt at friendliness; the clink of metal on brick continued. Eckhart wished he were holding one of those hammers.

Frankly, he hated painting. It didn’t tax his body; It taxed his soul. He put a piece of himself on every canvas, but the canvas didn’t thank him for the gesture. He was not some master poet who could converse with his painting, who could communicate his vision through his brush alone. It needed a lieutenant on the easel, a force that commanded the colors to conform. Such a leader could only be the artist himself, and so he would sliver off a piece of soul to create the painting. The workers' cracked hands were formed by the sun and the hammer, but Eckhart made the same cracks on his soul with every stroke of the brush. It was a self-demolition, slowly eating his spirit alive. But the more he was consumed, the more he understood. The clouds were fuller; light became more resplendent. He sent up his soul as oil paint offerings, and nature shone brighter as his reward.

However, when he was painting St. Boniface, he felt once again stuck in darkness. He poured himself into the portrait, but Boniface refused to cooperate. Eckhart felt as if he was becoming the Saint himself. He would adjust his habit till it became ugly again, he would keep that annoyingly guiltless expression on his face, and then he would stare right at Eckhart. Boniface sharpened his gaze like an axe, the axe. The painter would work his hands until they glowed like molten metal, trying to conform the Saint’s boundless spirit to a square frame. Boniface’s supposedly blameless serenity seemed more puzzled than anything, asking Eckhart why he took on the Herculean task of capturing holiness. Until this morning, Boniface simply eluded Eckhart’s strokes, undoing the work done a few motions before in the struggle between master and creation. But when Eckhart left today, Boniface’s serenity hollowed, axe gleaming in anticipation.

It was in the light of that hot noon, as Eckhart passed into the tavern, that he caught a glance of his phantom adversary. Boniface had followed him out of the church; the Saint’s expression seemed sourer than the tartest apple. Eckhart ordered a turnover and small black coffee, waiting in trepidation while the thick black slurry was poured into the cup. Adjacent, the pastry sat innocently. He sipped the bitter drink and raised the cake to his mouth, while his hunter sat ready. As he bit into sharp apples, Boniface struck. The axe crashed into his shins, causing him to drop the turnover in consuming fear. He looked in alarm as crimson liquid painlessly seeped into his pants, but he could still walk. Did he actually get me? Whose blood is this? As Eckhart looked over his shoulder, Boniface wiped the blade on his sleeve, eyes fiery with determination. Whatever he was attempting, that was only the first swing. Pushing himself up, the painter crumpled a few marks on the counter and grabbed his coffee before hurriedly moving to the door.

Shufflingly quickly towards the park, he stumbled over the roots of his napping tree. Sitting in the shade, he stared at the clouds. At least God had provided a natural barrier to the harsh sun. How harsh that light has become. Boniface swung the axe at Eckhart’s hands, and he spun to the ground from the blow, cup flying. The coffee mixed with fresh blood flowed from his hand, and the rocks knew the bitter taste. Eckhart knew no peace. The hammers could be heard for miles. Again, it struck Eckhart, this time in his eyes. He was blinded for a second by the assault, but on opening his eyes, he found that he could still see. He wished he couldn’t, though. The white cloud edges sharpened into cheekbones, and cirrus swept in as eyebrows. The horizon became full of faces, and they all took on Boniface’s countenance. Eckhart was surrounded by the sky.

I need to find cover. Realizing running was useless, Eckhart cowered beneath the oak, taking sanctuary in his resting place. Boniface had moved to the ground, closing in on the painter. Eckhart backed towards the tree, till the bark became his skin. He was afraid. Serenity painted Boniface’s face. The workers raised their hammers, and Boniface swung. Eckhart threw his head back.

He saw the boundaries of infinity, gilt as if by angels with a million pieces of gold leaf. The space Eckhart was floating through had some resistance to it, as if he were swimming. Huh, the universe is thicker than I thought. Birds flit around the circumference, dipping and diving around the edge as birdsong filled the heavens. As he listened to the choir of sparrows, it occurred to him that he was not only floating, but standing. He looked over the pinkish-red stone, covered in crevices, with some narrow mountains in the distance. He bent down to the ground and felt the surface, recoiling as he realized the surface was not stone but soft, with no sediment. In horror, he ran toward the rim of the surface, climbing up the slopes using the ridges in the terrain. Once he made it to the top, he looked back and saw that the whole surface was one giant disembodied palm. Shocked, he teetered backward and fell off into the void, staring up at the birds. The fist of the giant shook the air, fingers cracking after centuries of inertness. It sped towards the descending Eckhart, grasping to catch him. As it curled around him, he looked up again at the ring of birds and listened to their song of serenity.

—

Waking five hours later at dusk, he returned to the cathedral, completed the icon, and promptly left the town. In his haste, he left his studio apartment full of papers, oils, and other paints of varying color and quality, taking with him only his smock and a bag with a change of clothes. He did not need the rest. The next Sunday, parishioners were astonished to see the icon against the back left wall, with the Saint in an active pose. The kind monk swung his axe towards the tree with full force. No halo adorned his head, but his hands were encircled by two disks of gold.